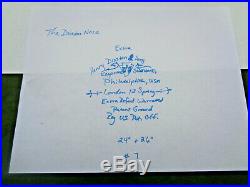

Disston Hand saws- Marked with. A 7 on bottom corner of both saw blades. London #12 Spring Steel Panel. BOTH ARE INCLUDED IN THIS SALE. Hand crafted in the early 1900’s (1896- 1917). Looked up the style on the history of Disston saws and found the same design of stamp and handle. The actual age was found out by the stamp on handle. The larger 26″ saw blade- 29 3/4″ Full Size faintly shows the mark -only found very slight U. Stamp and some other marks I could hardly read on it. The 24″Blade 28″ Full -was easier to read. It is also easy to see the year by the brass fittings and design of the carved wood. This was the finest saw they had made! I recreated what I saw on paper and wrote what was not shown from the stamp that listed the age of the saws. When you see what I wrote – the stamp is somewhat shaped like an egg. Henry Disston and Sons. Could see this design on the smaller saw- other saw was extremely faint! Both very nice condition considering this set was made 1896 -1917. Has rust – wear – paint – some chipping on handles(Larger one has tips of end rubbed off -please see pictures) – tried to show all but weren’t enough pictures to capture everything. The saw blades and handles are somewhat darker in person – the light from the sun room made them appear brighter. Many carpenters and saw users who take pride in having exceptionally well made and well finished tools, are users of this saw. 12 has a straight-hack, full width blade of Disston-made Steel. This blade is extra tempered and will hold its cutting edge longer than the ordinary saw. It is ground one gauge thinner than other hand saws, for special clearance, and therefore requires little set. The handle is made of selected applewood and is carefully carved and polished. This saw is of the best Disston material and workmanship and is very attractively finished. It is made in lengths from 16 to 30 inches with cross-cut or rip teeth. Further History grom Ditson & Sons, Keystone Saw Works. Disston and Sons, Keystone Saw Works. Workshop of the World (Oliver Evans Press, 1990). At its zenith, Henry Disston and Sons employed an average of 2,500 workers, covered sixty-four acres, and comprised sixty-four buildings. Until its sale to H. Porter in 1955, it was a family-run firm. It had sales branches in nine cities, including Tokyo, and a plant in Canada. Saws remained Disston’s best known product throughout its existence; indeed every imaginable sort of blade for cutting wood or metal was produced at the saw works. The process of creating a handsaw blade involved eighty-two steps. It began with the making of steel in crucible pots which were poured into molds that produced ingots. The ingots originally were flattened by screw-type vices; later steam pressured hammers were used. The process of flattening continued in the rolling mills, where large sections of rolled steel plate were routinely turned into saw plate steel. After teeth were cut in the steel “in the soft, ” the metal was tempered in a precision furnace before hardening in a bath, it was then heated again in a tempering oven and allowed to cool naturally. Tempering gave the steel elasticity (spring) and durability. The next step was “smithing, “hand-hammering the blade to perfect flatness and subjecting it to several stages of grinding and filing. Thus, when the saw was in use, the teeth cut a channel slightly larger than the width of the blade, which prevented the blade from binding in the channel. Disston produced wooden saw handles and the brass screws with which they were attached to the blades. This process involved eighteen steps. Handles were made from applewood logs, which were first cut to the proper thickness and then aged in the open air for three years. The applewood was then “ripped” cut, marked to pattern, sawed inside and outside, oiled, nose-fonned, sanded, varnished, carved, polished, bored, and split. Finishing the handles was one of the few jobs that women performed in the Disston works, (the company employed 195 women and 2,605 men in 1916). Disston During its peak years of production, Disston used some 35,000 files per year to sharpen saws. Thus, file-making machines and mechanical sharpening machines were important components of the Disston plant. Files, like saws, demanded the best hard steel available. The steel ingots for the files received a slightly different treatment in the rolling mills than those used to produce saws. The file ingots were reheated and rolled into large bars. These bars were cut into pieces, which in turn were rolled into bars of decreased diameter and increased length until they formed the size of file required. Once the desired thickness and widths were reached, the strip of steel traveled to the file works where it was cut into proper lengths. The file blank was then “tanged, ” the tang being the smooth, pointed end on a file which is usually fitted with a handle, although frequently it could be employed without a handle. This was done by heating one end of the file and forging a tang from it. The worker in this operation was seated before an automatic hammer with a small furnace close at hand. The temperature in the file oven was crucial to this operation, as too much heat would prevent the file from being properly teethed and too little heat would not allow the workman to successfully mold the tang. The files were put into air-tight boxes and placed in annealing ovens, which were set to a predetermined temperature. Once removed from the oven, the files cooled in the boxes, not in the open air. These processes caused the file to warp, or become uneven, so that it then had to be taken to the straightening department, and thence to the grinding department where the files were made perfectly smooth so that teeth could be cut evenly into them. The teeth were then cut into the soft metal with a chisel-like machine, and a final heating hardened the file. In all, Disston produced 50 types of files, some flat, some rounded, and with variable teeth that ranged from the rasp file to a fine file for aluminum. The Disston plant site is divided by Knorr Street into two main components. North of the Knorr Street gate on New State Road are the steel and power plants, and the rolling mills, to the south are the offices and production buildings. The steel plant consists of an armor-plate building, a steel-fumace building, and rolling mills. The armor-plate building had large dies that stamped out plates of steel for tanks in World War II. Making steel required raw iron and steel scraps which were stored in a large yard located next to the steel furnace building. The crucible pot method was used to melt the ore and scraps to form ingots. Adjacent to the steel-fumace building were the rolling mills, where the steel ingots were rolled into sheets of steel. The stack on the power plant, which dominated the Tacony landscape for years, was destroyed by an explosion in 1951 when workmen did not properly blow out the gas fumes from the stack before igniting the furnace. Except for the rolling mills and the annor-plate building, these structures are empty shells today. These include grindstone sheds, a hardening shop, lumber yard, file forge building, jobbing building, machine building, and production buildings for hand saws, long saws, circular saws and band saws. With the exception of the lumber yard and the grindstone sheds most of these buildings are still standing today. A small part of the site south of Knorr Street remains industrially active under ownership of Disston R. This company produces large circular saws for cutting hot steel. A small hardening shop, a torch-steel cutting shop, and a teeth-cutting and smithing shop function daily. More than twenty employees work under the direction of Roland Woehr. However, this factory at New State Road south of the Knorr Street gate is a shell of the once mighty Disston and Sons Keystone Saw Works. Unpublished manuscript, (Philadelphia, 1989). Philip Scranton and Walter Licht. “The File, Its History and Making, “. The Disston Crucible: A Magazine for the Millman, (January, February, March, April, 1914), [available at the Free Library of Philadelphia, Logan Square, Philadelphia]. Interview with Bob Bachman and Roland Woehr at Disston and Sons site by Harry C. Silcox, December 27, 1988. All very interesting history if you get the chance to check up on! The item “2 Early 1900’s Hand Saws # 12 Henry DISSTON & SONS, 24& 26 blade stamped 7″ is in sale since Friday, May 10, 2019. This item is in the category “Collectibles\Tools, Hardware & Locks\Tools\Carpentry, Woodworking\Saws”. The seller is “candysparrow” and is located in Greenville, New Hampshire. This item can be shipped to United States.

- Country/Region of Manufacture: United States

- Original/Reproduction: Antique Original

- Brand: Disston

- Featured Refinements: Vintage Saw