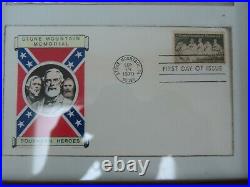

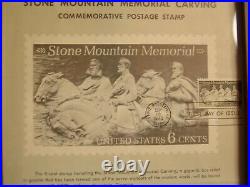

This is a listing for a Three (3) separate pieces of Stone Mountain Commemoratives consisting of the 1. POST MARKED HISTORY Stone Mountain Dedication Cover consisting of the 1925 Stone Mountain Silver Commemorative 50 Cent Coin and the Stone Mountain Dedication Day Medal by Medallic Arts Company postmarked May 9, 1970. A Stone Mountain Memorial Southern Heroes First Day Cover with the FIRST DAY OF ISSUE United States STONE MOUNTAIN MEMORIAL Six Cent (6 cent) STAMP. 1970 POST MARKED HISTORY COVER. This Postal Cover contains one (1) 1925 Stone Mountain Commemorative Silver 50 Cent Coin (Coin would grade MS 68 or higher). This Postal Cover also contains one (1) Stone Mountain Bronze DEDICATION DAY MEDAL by Medallic Arts Company. Also two (2) United State Postal Stamps cancelled on May 9, 1970. Only 100 Postmark History First Day Covers produced. DESCRIPTION of the 1925 Stone Mountain 50 cent coin. SILVER COMMEMORATIVE 1925 STONE MOUNTAIN 50 CENT contained within the POST MARKED HISTORY COVER is POSTMARKED MAY 9, 1970. Only 100 Postmarked Covers produced. SILVER COMMEMORATIVES 1925 STONE MOUNTAIN 50 CENT COIN. The 1925 Stone Mountain half dollar was struck to help raise funds for the completion of the massive carving honoring Southern Civil War heroes at Stone Mountain, Georgia. The project, which began in 1916, was plagued by numerous interruptions. In fact, it wasnt until 1970 that the project was actually completed, and that was only after the State of Georgia intervened. However, by the mid 1920s, with the hope of finishing the project in a timely manner still alive, the Stone Mountain Confederate Monumental Association decided to raise funds for the project via a commemorative coin. With strong support for the project from President Calvin Coolidge, a bill was easily passed on March 17th, 1924 authorizing the minting of up to 5 million half dollars in commemoration of the soldiers of the South. The models for the coin were furnished by Stone Mountains original sculptor Gutzon Borglum, who was fired soon after due to many disagreements with the Association. Still, his heavily modified designs were eventually approved on October 10, 1924. The 1925 Stone Mountain in the POST MARKED HISTORY Cover is mint perfect condition and would grade better than MS-68. DESCRIPTION of the Stone Mountain Dedication Day Medal. The DEDICATION DAY MEDAL. 1970 Stone Mountain Confederate Memorial Medal Bronze made by Medallic Arts Company. Brilliant Uncirculated 1970 Stone Mountain Confederate Memorial Bronze Medal from Medallic Arts Honoring the Completion of the Confederate Memorial Carving. This Historic Bronze Medal is approximately 1 1/2 in Diameter. The Obverse of Medal has Confederate President Jefferson Davis, General Robert E Lee, and General Stonewall Jackson on Horseback similar to the Actual Carving with Inscription “Stone Mountain Confederate Memorial and Date 1970″. The Reverse of Medal has The United States and Confederate States Flags with Stone Mountain in Background with Inscription “Duty, Honor, Courage and Unity Through Sacrifice”. DESCRIPTION of the two (2) stamp on the Post Marked History Cover. POST MARKED HISTORY COVER has two United States Stamps. The top stamp is a 1937 Four Cent (4 cent) stamp. Lee and “Stonewall” Jackson. The bottom stamp is a. DESCRIPTION of the Stone Mountain Memorial Southern Heroes First Day Cover with the FIRST DAY OF ISSUE United States STONE MOUNTAIN MEMORIAL Six Cent (6 cent) STAMP. This is a First Day Cover with the First Day of Issue canceled six cent (6 cent) Stone Mountain Memorial Stamp on a First Day Cover with the images of General Robert E. Lee, General Stonewall Jackson and President Jefferson Davis and the Confederate Flag with the inscription STONE MOUNTAIN MEMORIAL and SOUTHERN HEROES. The Stamp and Cover is Post Marked. FIRST DAY OF ISSUE. STONE MOUNTAIN COMMEMORATIVE 6-CENT STAMP. The 6-cent stamp honoring the Stone Mountain Carving, a gigantic bas relief in granite that has been termed on of the seven wonders of the modern world, will be issued September 19, 1970, at Stone Mountain, Georgia. Approximately the size of a football field, the carving shows the mounted figures of Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis and Stonewall Jackson. It is some 13 miles east of Atlanta and is the focal point of a 3,800-acre state park that is visited annually by more than two and a half million persons. The horizontal stamp, which shows the carving, will be printed in gray on the Giori Press. It was designed by Robert Hallock of Newton, Connecticut. Engravers are Edward R. Felver (vignette) and Howard F. Sharpless (lettering) of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. Collectors desiring first day cancellations may send addressed envelopes, together with remittance to cover the cost of the stamps to affixed, to the Postmaster, Stone Mountain, Georgia 30083. The outside envelope should be endorsed First Day Covers 6c Stone Mountain Carving Stamp. Orders for covers must not include request for uncanceled stamps. Cover request must be postmarked no later than September 19, 1970. And the date of. And the zip code. The Stone Mountain Commemorative United States Post Office Bulletin Board Notice is enclosed in a wood & glass frame. The Stone Mountain Commemorative United States Post Office Bulletin Board Notice and Commemorative Stamp are in perfect condition. Description of Stamps on Post Marked History STONE MOUNTAIN DEDICATION Cover of May 9, 1970. Lee and “Stonewall” Jackson who achieved fame as Confederate Army generals during the United States Civil War. The background features the Stratford Hall plantation which was the birthplace of General Lee. #788 1936-37 4¢ Lee and Jackson U. Bureau of Engraving and Printing. #788 was part of a 10-stamp series that commemorated Army and Navy heroes of the United States 5 stamps for each. Shown in the background of U. #788 is Stratford Hall in northern Virginia the birthplace of Robert E. Four generations of the Lee family lived in the plantation, including two signers of the Declaration of Independence (Richard Henry Lee and Francis Lightfoot Lee). #788 was issued during President Franklin Roosevelts administration. Roosevelt was involved in the process of every stamp issued during his presidency and had a sharp eye for detail and accuracy. But #788 was one time Roosevelt made an error. The image of Lee on the stamp shows two stars on his shoulder (representing his rank). Lee was a three-star general. This drew numerous complaints from collectors in Southern states, who thought the error was on purpose in order to diminish Lees legacy. The Post Office Department responded that the mistake had been only an accident, with the third star lost during the production process. Confederate Generals Honored on Federal Stamps. The 4¢ 1937 commemorative is a rare occurrence of a stamp featuring military leaders who took up arms against the United States. Lee joined the Army of the Confederacy because he couldnt bear the thought of taking up arms against his native Virginia. (Stonewall) Jackson served under Lee during the Civil War until Jacksons death at the Battle of Chancellorsville. Despite serving as Commander-in-Chief of Virginia forces, Robert E. Lee did not believe in the practice of slavery. 1951 3¢ Confederate Veterans Reunion. 11 x 10 ½. In the years after the Civil War ended, both Northern and Southern veterans began establishing their own local organizations to stay in contact with each other and provide aid to those veterans in need. In the North, Union veterans founded the Grant Army of the Republic in 1866. In the South, federal law prohibited rebel societies until 1878. However, several small Confederate veterans groups still organized during this time. On June 10, 1889, their representatives assembled in New Orleans and formed the United Confederate Veterans. Its constitution declared the organizations purpose as strictly social, literary, historical, and benevolent. The organization provided financial support for disabled Southern soldiers and Confederate widows and orphans. It also preserved mementos and records of service for its members. The first reunion of the United Confederate Veterans was held in Chattanooga, Tennessee, on June 3-5, 1890. Invitations were extended to veterans of both the Confederate and Union armies as well as the general public. The annual reunions were very popular. During their peak years in the early 1900s, membership reached 160,000 veterans organized in to 1,885 local camps. The UCV also produced a popular magazine that detailed events from the war and offered a section that helped veterans get in touch with each other. The UCV also supported Congressional acts in 1901 and 1906 that called for the inclusion of over 30,000 Confederate graves in the federal cemetery system. Membership in the UCV peaked in the early 1900s and began to decline as eligible veterans passed away. The last reunion was held in Norfolk, Virginia, in 1951. Three of the last 12 surviving Confederate veterans were in attendance. The reunions events included reenactment of the battle of the Monitor and the Merrimac. Sons of Confederate Veterans and United Daughters of the Confederacy were formed in later years and both groups are still active today. Stone Mountain Confederate Memorial. The largest high relief carving in the world. Located in DeKalb County, about ten miles northeast of downtown Atlanta, Stone Mountain is the largest exposed mass of granite in the world. Not surprisingly, the mountain has been a landmark for thousands of years. Granite from the mountain is considered high quality, and blocks quarried from its sides can be found on the steps of the U. In 1914, Caroline Helen Jemison Plane, head of the Atlanta chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), called for the creation of an organization to lead the construction of a memorial on the side of Stone Mountain. The UDC agreed, and the Stone Mountain Confederate Memorial Associaction (SMCMA) was incorporated in 1916. Samuel Venable deeded the north face of the mountain to the UDC that same year, with a stipulation that the memorial be completed within twelve years. Venable suggested hiring Gutzon Borglum to design and sculpt the memorial, and the SMCMA agreed with the suggestion. The design that Borglum came up with had. Followed by Confederate President. And a group of five generals, then 65 staff officers (each of the 13 Confederate states would chose five of their officers to honor) followed by a group of General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s cavalry. They supported the carving, but refused to contribute financially. Preparation of the mountain face and erection of scaffolding began in 1916, but U. And fundraising difficulties delayed the start of actual carving until 1923. Borglum had only completed Lee’s head when, in 1925, a dispute between he and the SMCMA led to him being fired. Borglum went on to supervise the carving of. Borglum was replaced by Augustus Lukeman, whose design envisioned two groups, one of four men on horseback, Robert E. And an unnamed color-bearer, and a second group which would later be dropped because of cost and time pressure. After removing Borglum’s work, Lukeman began work on his design in September 1926. Work was halted in 1928, however, when Venable refused to renew the lease on the mountain. Once again, only the head of Robert E. Lee had been completed. The unfinished memorial remained nothing but a tourist curiosity until 1941, when Georgia Governor Eugene Talmadge convinced the State Legislature to form the Stone Mountain Memorial Association (SMMA). Atlanta sculptor Julian Harris was hired to oversee completion of the work and the. Was assigned the task of providing labor, but. Intervened and interest in the project again waned. By the late-1950’s the state and the public were both ready to see work on Stone Mountain completed. The state and SMMA agreed to carve the images of Robert E. Lee, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, and Jefferson Davis on the mountain and to construct a plaza at its base. Walker Kirkland Hancock was hired to supervise the work, which resumed in September 1963. An estimated 10,000 visitors attended the memorial’s dedication on May 9, 1970, and the work was officially declared complete in 1972. The entire carved surface of Stone Mountain measures three acres. The carving of the three men towers 400 feet above the ground, measures 90 by 190 feet, and is recessed 42 feet into the mountain. The deepest point of the carving is at Lee’s elbow, which is 12 feet to the mountain’s surface. The park land around the Memorial now includes golf courses, a railroad, an artificial lake with a Mississippi river boat, an aerial tram to the summit, a museum of automobiles, and exhibits of Southern history. For the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, Stone Mountain Park hosted cycling, tennis and archery events. Stone Mountain Memorial half dollar. Struck in 1925 at the. The coin features a depiction of Confederate generals. On the obverse and the caption: “Memorial to the Valor of the Soldier of the South” on the reverse. The piece was also originally intended to be in memory of the recently deceased president. But no mention of him appears on the coin. In the early 20th century, proposals were made to carve a large sculpture in memory of General Lee on Stone Mountain, a huge rock outcropping. The owners of Stone Mountain agreed to transfer title on condition the work was completed within 12 years. Borglum, who was, like others involved, a. Member, was engaged to design the memorial, and proposed expanding it to include a colossal monument depicting Confederate warriors, with Lee, Jackson, and Confederate President. The work proved expensive, and the Association advocated the issuance of a commemorative half dollar as a fundraiser for the memorial. Congress approved it, though to appease Northerners, the coin was also made in honor of Harding, under whose administration work had commenced. Borglum designed the coin, which was repeatedly rejected by the. Commission of Fine Arts. All reference to Harding was removed from the design by order of President. The Association sponsored extensive sales efforts for the coin throughout the South, though these were hurt by the firing of Borglum in 1925, which alienated many of his supporters, including the. United Daughters of the Confederacy. Because of the large quantities issuedover a million remain extantthe Stone Mountain Memorial half dollar remains inexpensive compared with other U. The first European-descended settlers inhabited the land around. Today in the east Atlanta suburbs, around 1790. They called the large outcropping, about 2 miles (3.2 km) long and 1,686 feet (514 m) high, “Rock Mountain”. First named it Stone Mountain in 1825. The town of New Gibraltar was founded nearby in 1839; its name would be changed to Stone Mountain by the. From about the time of the. The mountain was used as a quarry; this would not entirely cease until the 1970s. John Gutzon de la mothe Borglum usually called. In 1867, to one of several wives of a Dane who had converted to. As a boy, Borglum lived in various places in the Far West. Turning to art as a career, he attended the. San Francisco Art Academy. Whom he met, Borglum switched from painting to sculpture in 1901. Won a gold medal at the 1904. Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 1914, editor John Temple Graves wrote in the. Suggesting the establishment of a memorial to. On Stone Mountain, from this godlike eminence let our Confederate hero calmly look history and the future in the face! Others who called for the establishment of a Confederate memorial there included William H. Terrell, an Atlanta attorney who believed that while the North had spent millions of dollars on monuments to the. The South had not sufficiently honored Confederate heroes. Also active in the early days of the Stone Mountain proposal was Helen Plane (18291925), who had been a belle from Atlanta before the war, and whose husband had given his life at the. She devoted the remainder of her life to preserving the memory of the Southern cause. The release of the film. The Birth of a Nation. In 1915 sparked increased interest in the Confederate cause in the South. Plane, who was lifetime honorary president of the Georgia organization of the. (UDC), asked Borglum to carve the image of General Lee on the mountain. The Stone Mountain project was initially a UDC endeavor. Officials originally contemplated a monument of perhaps 20 feet (6.1 m) by 20 feet (6.1 m). He proposed a much larger sculpture, 200 feet (61 m) high and 1,300 feet (400 m) long, and drew up plans in his. He envisioned a huge depiction of the Confederate army, including artillery and infantry, as well as 65 Confederate generals, five to be nominated by the governor of each Southern state. In 1917, the Stone Mountain Confederate Monumental Association (the Association) was founded to publicize and raise funds for a colossal sculpture at Stone Mountain. Venable and his family, owners of the land, agreed to deed it over for a monument, on condition that if the project was not completed in 12 years, title would revert to them. A formal dedication took place in May 1916; the preliminary work was interrupted by the US entry into. Another organization which took an interest in the Stone Mountain work was the recently revived. Of which both Venable and Borglum were members. The Klan, through much of the 20th century, held regular encampments on or near Stone Mountain. Plane, in a 1915 letter to Borglum, stated that the original Klan had saved the South from “Negro domination” in the. And suggested that the design include a small group of Klansmen in robes, seen in the distance, approaching. Beginning in 1920, the project slowly came under the control of Atlanta businessmen, brought in to aid with the massive fundraising, and the UDC became marginalized. The work on the sculpture resumed on June 18, 1923, when Borglum began carving Lee’s figure into the mountainside; he planned for General. To be close by Lee. Borglum’s plans were for a huge sculpture depicting the Confederates, a memorial hall hewn from the granite at the base of the mountain in which artworks and artifacts could be displayed (as well as rolls of honor listing the contributors) and a giant amphitheater nearby. Instead, the scope of the project was scaled back, though different sources give varying cost estimates and dimensions. Two men each sought credit for coming up with the idea for a coin. Webb, executive secretary of the Association, said he had thought of it after finding an. Alabama centennial half dollar. At home; journalist Harry Stillwell Edwards made a similar claim and apparently collected a reward from the Association. Borglum’s design for Stone Mountain. On November 16, 1923, Edwards wrote to Bascom Slemp, secretary to President. Edwards arranged a meeting between the President and himself, association president Hollins N. Randolph an Atlanta lawyer and direct descendant of early president. President Coolidge agreed to support authorizing legislation for a Stone Mountain coin. Borglum later stated that the Association asked him to write to people in Washington because of his contacts in the Republican Coolidge administration. He wrote to the powerful Republican Massachusetts senator. Urging him to support legislation for a Stone Mountain commemorative coin; the appeal apparently worked, as late in 1923 the committee chairmen having jurisdiction over coinage. In the Senate and. In the House of Representatives, introduced legislation for a Stone Mountain Memorial half dollar. McFadden later wrote that he sponsored the legislation because of his friendship with Borglum. With the threat of sectional opposition if the coin only honored the South, the bill’s sponsors included language making the new half dollar also in memory of the recently deceased Harding (an Ohioan), during whose presidency the renewed work had begun. The bill passed by. In the House on March 6, 1924, and in the Senate five days later; Coolidge signed it on March 17. The bill authorizing the coin read. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That in commemoration of the commencement on June 18, 1923, of the work of carving on Stone Mountain, in the State of Georgia, a monument to the valor of the soldiers of the South, which was the inspiration of their sons and daughters and grandsons and granddaughters in the Spanish-American and World Wars, and in memory of Warren G. Harding, President of the United States of America, in whose administration the work was begun. Borglum was busy between the passage of the bill and the end of May 1924, first working on the Children’s Founders Roll medal, and then the half dollar. The Children’s Founders Roll was open to white children up to the age of 18 who contributed one dollar to the building of the monument. Borglum must still have been fine-tuning the monument’s design; Jackson’s posture on the medal differs from that on the coin. Unlike the issued coin, Borglum’s models showed the front part of Davis’s horse, although the Confederate president is unseen, and marching soldiers appear in the background. Borglum met with Treasury Secretary. Who questioned first why. In God We Trust. Appeared directly over Lee’s head; Borglum responded that it was to pay tribute to the Confederates’ faith. Mellon then asked what the thirteen stars on the obverse represented; Borglum replied that those on the north side of the. Could consider them to represent the thirteen original colonies (those south of it, the implication was, could consider them to be a tribute to the Southern states). Mellon laughed and gave preliminary approval. On July 2, Mellon showed the designs to President Coolidge; they were then sent to the. For its members’ opinions. Borglum’s original models for the half dollar. According to numismatists William D. Colbert, “Borglum, to put it mildly, was a temperamental artist who managed to offend most everyone with whom he worked”. They note that “Borglum’s past insolence had not left him in the good graces of the art community” and his designs met a hostile reception at the commission. Rejected Borglum’s initial design on July 22, eight days after they were received. The inscription on the reverse included a tribute to Harding; Fraser deemed it inartistic. Borglum submitted a second set on August 14, this was again rejected; the commission criticized the design, which seemed to be only a segment of a larger one, rather than specifically designed to fit a half dollar. Borglum wanted to ignore what he deemed “damn fool suggestions”, but the Association threatened to fire him if he did not complete the coin. Borglum was concerned the reverse was still too crowded, and proposed leaving off the eagle, but space was saved when Coolidge did not like the reference to Harding, and it was omitted. With the eagle still in place on the reverse, Fraser finally approved the designs on October 10, 1924. In all, Borglum made nine plaster models for the design. Even though all necessary approvals had been received, the. Refused to proceed with preparations because of the lack of the mention of Harding, which it believed was congressionally mandated. Borglum wired Coolidge on October 31, notifying him of the problem; the President confirmed his approval of the design the following day. Despite the support of the federal government for the coin, the. Grand Army of the Republic. (GAR), an organization of. Civil War veterans, tried to prevent the issuance of a coin they believed honored treason by lobbying in late 1924 and early 1925. Work on the sculpture slowed (the head of Jackson was then being carved) because of the sculptor being distracted by designing the coin, flaws in the rock on Stone Mountain, and the fact that the Association had ceased fundraising efforts in anticipation of a campaign to sell the coin. Revenues from the medal were not sufficient to meet expenses. The obverse of the half dollar depicts Confederate generals Lee and Jackson, the latter with head bare, mounted on horseback. Although both Lee and Jackson were respected in the North, Davis would not have been acceptable on a federal coin, and he was omitted, although he appears on the Children’s Founders Roll medal which Borglum adapted for the obverse of the half dollar. There are thirteen stars in the upper field of the obverse; they represent the thirteen states which either joined the Confederacy or had Confederate factions. Borglum’s initials, “GB”, are found on the extreme right of the piece, near the horses’ tails. The reverse depicts an eagle with wings stretched, representative of liberty, perched upon a mountaintop. There are 35 stars in the field, supposedly to represent the number of states at the start of the Civil War, although there were in fact 34 in 1861, and there were 35 states only from 1863 to 1864, between the admissions of West Virginia and Nevada. Writing in 1971, noted that the half dollar represents an unusual circumstance in American art, where a designer uses a coin as a. Or small-scale model of a work to be completed. Vermeule considered the children’s medal a better work of art, due to the inclusion of Davis. He believed that Borglum’s original design, before its rejection by the Commission of Fine Arts, was superior, as it included a sense of motion through the depiction of marching soldiers in the background, balanced by the inclusion of the head of Davis’s horse, though the Confederate president himself is unseen. According to Vermeule, the original design “would have made a magnificent coin, an unusual compression of monumentality and power into a limited and unorthodox historical space”. Of New York converted Borglum’s models to coinage dies. The first 1,000 Stone Mountain Memorial half dollars were struck on a medal press at the. On January 21, 1925, the 101st anniversary of General Jackson’s birth; Borglum and officials of the Association were present. The first piece struck was mounted on a plate made of gold mined in Georgia for presentation to President Coolidge. The second was mounted on a silver plaque, and presented to Secretary Mellon. The remainder of the first thousand were placed in numbered envelopes; some were presented to officials or those involved in the Stone Mountain project. Between January and March 1925, that mint struck 2,310,000 of the authorized mintage of 5,000,000, plus 4,709 pieces reserved for inspection by the 1926. Although the Association unveiled the completed head of Lee on January 19, 1924 (the general’s birthday), within months, its relations with Borglum had become strained. Technical problems over the medal and the work on the mountain caused tensions, and political differences between Borglum, a Republican, and Randolph, an active Democrat, led to poor relations between the two. Borglum, Venable, and Randolph backed different KKK members for national leadership. Randolph ridiculed the suggestion, stating that it would allow Borglum to carve “whatever he pleased on the mountain”. Borglum accused Randolph of using donations for his own benefit, and spending freely on an expense account. These dissensions became public, and in February 1925, the Association fired Borglum. Randolph stated, as one reason for dismissing the sculptor, that Borglum had taken seven months to design the coin, when, he said, any competent artist could have done it in three weeks. He accused Borglum of delaying so that the Association would be embarrassed. According to Freeman, despite all the points of conflict between Borglum and the committee, it was actually the commemorative coin that ended his career at Stone Mountain. Upon being dismissed, Borglum wrecked his models for the monument; the Association sought to have him jailed for destruction of property. Borglum was addressing the ladies of the Atlanta chapter of the UDC when his assistant, Jesse Tucker, burst in and hurried him out the door with a minimum of explanation, only moments before a sheriff’s deputy arrived to serve the warrant. He left the state, but was arrested in. Though quickly allowed bail, and the Association abandoned extradition proceedings. Freed, the sculptor soon took up a project in South Dakota. The publicity surrounding these events hurt the Association’s fundraising, as did allegations that the Association had misused hundreds of thousands of dollars put aside for the project. As replacement sculptor; all of Borglum’s work was eventually blasted away. Despite the dispute with Borglum, the Association proceeded to market the half dollars; it hired New York publicist Harvey Hill to run the campaign. The Association hoped for the opportunity to present the first coin to President Coolidge in person as a means of overcoming the bad publicity; White House officials warily declined, writing that “no good purpose would be served by a formal presentation”. They were sent to 3,000 banks by the Federal Reserve, with the proceeds from sales credited to the Association. White Southerners applauded the piece as symbolizing sectional reconciliation, the federal government paying homage to its Confederate heritage. The coins were to be distributed through banks, and the Federal Reserve System cooperated by moving coins as needed, though at the Association’s expense. The Association set up local affiliates, with organizations throughout the South, as well as Oklahoma and the District of Columbia. Each state’s governor served as nominal head of the organization within his jurisdiction; on July 20, 1925, at a meeting of the. Conference of Southern Governors. Called for the purpose, they (or their representatives) resolved that the Association allocate sales quotas among the states on the “basis of white population and bank deposits”. The overall drive to sell half dollars was dubbed the “Harvest Campaign” and began with the governors’ meeting in July 1925. Told his colleagues that the “South would be eternally disgraced if it failed to accept the challenge” of meeting the sales goal of 2,500,000 coins; nevertheless, the governors devoted little time to the campaign. Although volunteer enthusiasm was essential to the Association’s plans in the Harvest Campaign, it did not rely on it at the higher levels; the state chairs were compensated, both by salary and commission. Gibbes, clerk of the. South Carolina House of Representatives. The quota for Florida was 175,000 coins, with each town and city apportioned its share. Groups underwrote local quotas. Nevertheless, Hyder and Colbert suggested that there was a general lack of more ladies such as Mrs. Bass; many municipalities had trouble finding local chairs. Outside the South, sales were promoted by three professional publicists hired by the Association. To keep public interest high, the Association released Lukeman’s conceptions for Stone Mountain, which were on a smaller scale than Borglum’s. Lukeman conceived a scaled-down concept, of the three Confederate leaders on horseback. Despite the campaign, sales were slower than expected. In late 1925, the Association offered Northern banks a commission of seven cents a coin; it is uncertain if any took up the offer. The continuing opposition of the GAR to the coins dampened sales in the North, and there was considerable criticism of the coin issue in newspapers. Counterstamped Stone Mountain Memorial half dollar. One means of fundraising that Harvest Campaign administrators decided on was to. Some of the coins for sale at premium prices. The letters and numbers are believed to have been punched by the Association, as they are almost entirely uniform. Some were given a state abbreviation and a number, and were sent to be auctioned in various towns. Which town got which number was the luck of the draw. Others were marked with U. And a state abbreviation, together with a number which probably represents a membership or chapter number. These were intended for presentation to members deserving of special honor, such as an outgoing president. They did not sell well, as the Association had alienated many UDC members over the firing of Borglum. The Association also announced a program for sale to the. Sons of Confederate Veterans. Were puzzled over by collectors for many years; A. Steve Deitert in the January 2011 edition of The Numismatist identified the markings as “Gold Lavalier” and “Silver Lavalier”. Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. Those outside the South could obtain coins by orders passed through local banks. A bank in St. The Association called an end to the Harvest Campaign as of March 31, 1926, most likely because the sales did not justify the continued salary expenses. Coins remaining at banks were to be sent to the Federal Reserve, and any credit balances remitted to the Association. With a price increase and the end to the campaign, sales plummeted. Total sales from the Harvest Campaign were about 430,000 pieces. One exception to the drop in sales was a drive in New York under the sponsorship of Mayor. Then a prominent investor and later a counselor of presidents, was honorary chairman of the organizing committee, and personally subscribed for some of the pieces. The Atlanta chapter of the UDC in 1927 published a brochure accusing the Association of wrongfully firing Borglum and wasting between a quarter and a half million dollars. An audit of the Association’s books was performed in 1928; the examiners found its records in good order, excepting those regarding the Harvest Campaign, which were inadequate. The audit found that for every three dollars of revenue brought in from the half dollars, two were paid out in expenses, a ratio Hyder and Colbert called “incredible”. Of the total sum raised by the Association, only 27 cents of each dollar went to the carving. Venable stated that the Stone Mountain monument had “developed into the most colossal failure in history”. The Association was discredited by the results of the audit; the Georgia Senate voted to accuse it of gross mismanagement of funds. Randolph resigned when Venable made it clear he would not negotiate an extension of the twelve-year deadline unless he did. The Atlanta lawyer had begun a political career; the scandal finished it. With funds drying up, the Association stopped work on Stone Mountain on May 31, 1928, and when negotiations failed, the Venable family successfully sued to regain the property. Borglum was now a folk hero in Atlanta; he was called upon to return to Stone Mountain in the early 1930s, but busy with Mount Rushmore, he did not. At the time of Borglum’s death in 1941, no work was being done on Stone Mountain. The sculpture, which depicts Lee, Jackson and Davis, and bears only a resemblance to Borglum’s original design, was dedicated in 1970. At 90 feet (27 m) by 190 feet (58 m), it is the largest relief sculpture in the world. In 1930, Secretary Mellon reported that although no Stone Mountain Memorial half dollars were held by the Mint, it was his understanding that large quantities of the piece were in the possession of banks. Eventually, arrangements were made to return a million half dollars to the Mint for melting. In spite of this, the State of Georgia still had Stone Mountain half dollars for sale at its exhibit at the 1933. Century of Progress Exposition. Many more were dumped into circulation in the 1930s. A total of 1,314,709 Stone Mountain Memorial half dollars were distributed, after deducting those pieces melted. Stone Mountain and the Monument Man. On Nov 5, 2018. When National Socialism came to power in Germany in 1933, it sought an ethnic and cultural cleansing of the country. Jewish culture and art was not considered fully human and underwent a purge. Once Nazi Germany started World War II in 1939, it also sought the same purge for all of Europe. Art considered Germanic was confiscated from all over Europe and brought to Germany. Adolf Hitler planned to create a massive museum in his home town of Linz, Austria, the Furermuseum, which he envisioned to become the cultural center of Europe. As with Jewish culture, Slavic culture was also considered not fully human and was to be purged. Polish culture was considered degenerate and was marked for destruction when the Nazis invaded Poland. The Poles were the next group of people marked for extermination after the Jews so that the Nazis could expand the Third Reich into that territory under their policy of L. To create living space for Germans. The Royal Castle in Warsaw, which was the home of Polish kings for six centuries, the seat of parliament, and a national treasure full of artwork, was deliberately bombed by the Nazis under direct orders from Hitler. The Nazis also shot at civilians, toppled monuments, and leveled historic buildings. Special fire units burned Polands libraries. The Nazis bored holes in the foundation of the castle in October 1939 creating a threat of complete destruction. This was finally accomplished by the Nazis after the Warsaw Uprising in August 1944 by detonating those explosives. In Cracow, the altarpiece of St. Marys Basilica was confiscated and taken to Berlin because it had been created by a German artist, although it had been commissioned by the king of Poland. Once the United States entered the war, the American Commission for the Protection and Salvage of Artistic and Historic Monuments in War Areas was created. It was also known as the Roberts Commission, after Supreme Court Justice Owen Roberts, who was its chairman. Army also established a program called Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFAA). Monument can be defined as a memorial stone or a building erected in remembrance of a person or event, and so it was used in this context. MFAA assigned monuments chiefs to the various U. Army groups to protect cultural treasures in war zones and also to return those stolen by the Nazis. These men later became known as the Monuments Men. One example of their work was to create a map of Florence, Italy, for Allied bombers marking the monuments so that they would not suffer any damage. The Allied target in Florence was the railroad station, which was being used by the Nazis. As a result of this map, only the railroad station was bombed and nothing else was damaged. However, the Nazis looted the artwork there and blew up the bridges, the entrances of which had been designed by Michelangelo. The explosion also destroyed nearby Medieval buildings and towers. One of the Monuments Men was Walker K. He was born in St. Louis, Missouri in 1901. He started his higher education at the School of Fine Arts at Washington University in St. Louis, but after a year, he transferred to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, where he studied from 1921 to 1925 with the sculptor Charles Grafly. Hancock was then awarded the Prix de Rome fellowship and studied at the American Academy in Rome, Italy from 1925 to 1928. Upon his return from Rome, he was made the head of the sculpture department at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1929 upon the recommendation of Grafly. Hancock was drafted into the Army at the beginning of World War II. He was placed in the Medical Corps and was trained at Camp Livingston, Louisiana as a medic. He was later transferred to the Army War College in Washington, D. And designed the Air Medal. He was then transferred to the Pentagon and given a promotion to First Lieutenant. While he was there, he learned of the work of the MFAA and requested and received a transfer there. Hancock contributed greatly to the work of the Roberts Commission, which began on the continent of Europe after the Allied liberation of Normandy and the Allies subsequent advances. He was promoted to Captain and assigned to the First Army. He compiled a list for the Commission of monuments in France in need of protection. He witnessed such things as the destruction of Louis XIV furniture by the Nazis, who then used cheap modern furniture, which was more to their liking. He also found Rembrandts. Rolled up in a wooden housing. He helped to save the Chartres Cathedral in France from possible destruction. Twenty-two sets of explosives had been placed in nearby bridges and other structures by the Nazis, which were removed. Hancock found that the Cathedral in La Gleise, Belgium had been severely damaged during the Battle of the Bulge, but that the statue of the. Madonna of La Gleise. When he urged the townspeople to move the statue to safety for its protection, they protested. He then convinced them to go to the Cathedral to take a look at the statue. When they did, a portion of the roof of the structure fell. This convinced them to move the statue to safety, which Hancock supervised. He found the Cathedral at Aachen, Germany to be severely damaged by warfare. Charlemagne had ruled from Aachen beginning in 800 AD and the Palatine Chapel in the Cathedral had been used for the coronation of German kings and queens for six hundred years starting in 936. The works of art there had been removed by the Nazis and those were among many others which Hancock, with the other Monuments Men, recovered. The Monuments Men found that the Nazis hid paintings in mines in Germany for transfer to Linz. Hancock and the others helped to recover these paintings and return them to where they came from before the war. The Aachen Cathedral treasures were found in a mine in Siegen along with the original manuscript of Beethovens Sixth Symphony among many other priceless items. While he was in Weimar, Hancock encountered a Jewish chaplain who was conducting memorial services at Buchenwald, but did not have a Torah to use in them. Hancock provided him with one which had been found in a SS headquarters. At the end of his time in Germany, Hancock was placed in charge of the archives at Marburg University. The accomplishment of the MFAA were depicted in the motion picture. Which was released in 2014. The character Sergeant Walter Garfield depicted in that movie was based on Hancock. John Goodman was chosen for the role because he is a St. Louis native, as was Hancock. Hancock was the sculptor of many acclaimed monuments in his lifetime, including the World War I Memorial in St. Louis, the Pennsylvania Railroad War Memorial in Philadelphia, the statue of General Douglas MacArthur at the U. Military Academy in West Point, the statue of James Madison at the Library of Congress in Washington, the statue of John Paul Jones at Fairmount Park in Philadelphia. In the High Altar at Washington National Cathedral, the President Dwight D. Eisenhower Inaugural Medal, the bust of Andrew W. Mellon at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, the busts of Chief Justices Earl Warren and Warren E. Burger in the U. Supreme Court Building in Washington, and the busts of Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey and Presidents Gerald R. Ford and George H. Bush in the U. Capitol Building in Washington, among many, many others. However, he was also the sculptor of the worlds largest carving, the Stone Mountain Memorial in Stone Mountain, Georgia. The mountain is made of Stone Mountain granite and this mountain is the only place in the world where this kind of granite is found. This carving, which is on the side of the mountain, was inaugurated by the Stone Mountain Monumental Association and was begun in 1925 by sculptor Henry A. It depicts Confederate heroes President Jefferson Davis, General Robert E. Lee, and Lieutenant General Thomas J. However, lack of funding brought the work to a halt in 1928, at which time only the head of General Lee was completed. The subsequent Great Depression prevented any further work and Lukeman died in 1935. The organizations board selected Hancock to complete the carving and work resumed under his direction in 1964. By this time, Hancock was living in Gloucester, Massachusetts. This caused some opposition to his appointment on the basis that a Yankee had been selected to complete the Confederate memorial. However, not only was Hancock originally from Missouri, but, he related in his. That both of my grandfathers had fought in the Confederate army, that my father was one of the highest officers in the Sons of Confederate Veterans, and that my mother had been very active in the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Hancock was certainly no Yankee. I first visited Stone Mountain in July of 1969. The work on the carving was nearing completion at that time and the noise from the blasting was very loud and could be heard throughout the park. The park was a Confederate memorial park in those days. There was a Confederate Hall with exhibits about the history of the War Between the States and an electric map, the War in Georgia. There was also a Memorial Hall, with relics from the war, both Confederate and Union. There were also buildings from ante bellum plantations in the state and a train ride around the mountain. The trains were pulled by replicas of the. The two engines from the Great Locomotive Chase in Georgia in 1862. While the final touches on the carving were not completed until 1972, it was essentially completed by 1970 and the dedication took place on May 9 of that year. I was present for the dedication that day and was glad to see the monuments final completion after four and a half decades. The theme throughout the dedication was reunion and renunciation of sectionalism. The benediction was delivered by a black minister, who said in his prayer that he thanked God for Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, Jefferson Davis, Abraham Lincoln, and Ulysses S. This was the prevailing attitude during the entire time monuments to Confederate and Union soldiers of the war were being dedicated. It was that both the North and South erected monuments to their respective war heroes in a reunited nation, and this helped heal the nation. Many examples of this over the years can be given, but I will let one suffice. The monument to the 128. New York Infantry Regiment on the Cedar Creek Battlefield in Virginia was dedicated on April 14, 1912. When the regiments veterans arrived for the dedication, the United Confederate Veterans camp in the nearby town of Strasburg held a dinner for them and put them up in their homes. Both the veterans of the 128. New York and the local Confederate veterans attended the dedication and considered the monument one to a reunited nation. I only heard about objections to the carving once while I was there. On a newscast the night after the dedication, a newscaster reported that some were saying the carving was wrong because of slavery. He answered it by quoting from a letter which General Robert E. Lee wrote to his wife from Fort Brown, Texas on December 27, 1856, in which he said: In this enlightened age there are few, I believe, but will acknowledge that slavery as an institution is a moral and political evil in any country. It is useless to expiate on its disadvantages. He gave this as the answer to the objection and dismissed the objection with this fact. However, a contrary spirit has now reared its head. The Cultural Marxist mentality is now sowing division and demanding that Confederate monuments be removed, or, as in the case of the Stone Mountain Memorial, destroyed. Its adherents are toppling monuments, just as the Nazis did, in order this time to purge Southern culture in particular and American culture in general. It would be a shame to see the greatest monument of one of the Monuments Men, Walker K. Hancock, who died in 1998 and did so much to save Europes monuments and create many here in the United States, be destroyed. Today, Confederate Hall has been made over into a museum of the ecology of the area and no longer lives up to its name. Have also been replaced with modern engines, so the purge of the park has already begun. One of the arguments for removing the Stone Mountain carving is that the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan used to hold rallies on the mountain. For February 13, 1973 recorded that, on Lincolns birthday that year, a group of neo-Nazis wearing swastika arm bands and white helmets placed a wreath at the Lincoln Memorial and hailed Lincoln as a champion of racial separation. They then put up their arms in Hitler salutes and marched around the corner to disperse with ritual shouts of White Power! Any study of Lincolns racial views shows that he favored the supremacy of the white race over the black and the colonization of blacks outside the United States. I saw a pamphlet published by the United Klans of America in the 1970s which quoted from Lincoln to support its white supremacist views. If the same mentality which is being applied to Confederate monuments were applied here, the removal or demolishing of the Lincoln Memorial would be advocated. However, a double standard is being applied here and Lincolns white supremacist and cultural cleansing views are being ignored. Those who are defending the historic monuments which are under attack from Cultural Marxism are the monuments men and women of today. We need more of them. People who think otherwise should heed the following words of Walker Hancock, which he stated in his. Although I have lived an exceptionally happy life, continually accompanied by good fortune, I possess, of course, my share of painful memories some of these tragic ones, indeed. However I have clung to the prerogative perhaps, in old age, the necessity of dwelling as little as possible on such subjects. The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europes Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War. New York: Alfred A. Edsel with Bret Witter. The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves, and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2009. Hancock with Edward C. A Sculptors Fortunes: Memoir. Gloucester, MA: Cape Ann Historical Association, 1997. Hancock, Experiences of a Monuments Officer in Germany. 5 (May 1946): 271-311. Life and Letters of Robert Edward Lee: Soldier and Man. Harrisonburg, VA: Sprinkle Publications, 1978 [1906]. John Saar, Rites at Lincoln Memorial Attract 200 on Birthday. February 13, 1973, B1, B4. The Rape of Europa. Written and directed by Richard Berge, Nicole Newnham, and Bonni Cohen. Menemsha Films with Actual Films, Agon Arts & Films, and Oregon Public Broadcasting, 2006. Directed by George Clooney. Culver City, CA: Columbia Pictures and Fox 2000 Pictures with Smokehouse Productions, 2014. Duskin is from Northern Virginia. He has a B. Degree in history from American Christian College, Tulsa, Oklahoma and a M. Degree in international relations from the University of Oklahoma. He worked for 22 years as an Archives Technician at the National Archives in Washington, D. He has also worked as a Writer for the U. Taxpayers Alliance in Vienna, Virginia and as a Research Assistant for the Plymouth Rock Foundation in Plymouth, Massachusetts. He has a strong interest in and devotion to history and is active in a number of historical organizations. The item “1970 Post Mark History Stone Mountain 50 Cent Coin & Dedication Day Medal Cover” is in sale since Friday, September 27, 2019. This item is in the category “Stamps\United States\Covers\Postal History”. The seller is “bohannan-one” and is located in Auburn, Alabama. This item can be shipped to United States, Mexico, Bermuda.

- Topic: Stone Mountain

- Certification: Uncertified

- Quality: Used

- Grade: Ungraded

- Denomination: 6 Cent

- State: Georgia

- Place of Origin: United States